Sunday, September 30, 2018

Self-Care A-Z: Self-Care Is Practicing With Purpose

from The New Social Worker Online — the professional social work careers magazine https://ift.tt/2NcrmzI

Dive Seasons in Papua New Guinea

Occupying the eastern half of New Guinea, the world’s second largest island after Greenland, Papua New Guinea sits high atop almost every diver’s bucket list. But in a land that spans 178,000 square miles (461,000 square kilometers), you’ve got to know where to go — and when — to get the most bang for your diving buck. With no highways spanning the entirety of the country’s rugged terrain, dive resorts in PNG give new meaning to the word “remote,” reachable only by small plane in many cases. Once you’re there, you’re there — and if it’s the right time of year, you’ll be happily stranded among some of the world’s best dive sites. Here’s our guide to the dive seasons in Papua New Guinea, focusing on the main areas.

Tawali

A wide peninsula juts out of Papua New Guinea’s southeastern corner, pointing like a finger to Milne Bay, home of Tawali Dive Resort. To get there, one must fly from the capital city of Port Moresby to Alotau. From there it’s a 90-minute bus ride through the countryside to small dock, where a boat awaits to make the final 20-minute journey to the resort. Milne Bay is most well-known for muck diving, but there are manta-cleaning stations and WWII wrecks on hand as well. Sitting on the north coast at the tip of the peninsula, Tawali is mostly sheltered from prevailing southeast winds. So even if the winds are blowing, visitors can still dive the protected northern sites. If the air is calm, divers have access to a plethora of sites south and southeast of the resort. Nonetheless, the very best time to visit this area of PNG is from October through March, when visibility is the best and the skies are relatively calm. Strong winds in February make getting to most dive sites a challenge.

Tufi

In Oro Province, which makes up most of the peninsula’s northern shore, Tufi Resort perches atop a spectacular green fjord with sweeping views of the water below. Just as with other PNG resorts, Tufi is quite remote. You’ll arrive via small plane from Port Moresby, which lands on a nearby runway, paved by Tufi’s owners to make the resort more accessible. It’s a short walk or quick car ride to the resort from there. Although there is diving in the fjords, Tufi’s real draw is the spectacular offshore reefs, five to 10 nautical miles offshore, so remote that many remain unexplored. On good-weather days it takes from 15 minutes to over an hour to reach some sites, and steady onshore winds for part of the year make them nearly inaccessible. The very best time of the year to visit is during wet season, from November to March.

Walindi

Walindi Plantation Resort sits on the shores of Kimbe Bay on New Britain, a PNG satellite island just north of the mainland. To get here, you’ll fly from Port Moresby to Hoskins Airport, also called Kimbe Airport. From there it’s a 50-minute drive to the resort. Kimbe Bay is best known for spectacularly healthy coral gardens and walls, and guests can reach even further-flung destinations onboard the resort’s liveaboard dive boats, the MV FeBrina and MV Oceania, which offer 8- through 10-night itineraries. The best time of year to visit Walindi is April through June and August through December.

Rabaul

Rabaul, also on New Britain at its northern tip, is best known for fantastic WWII wreck diving. Most sites are relatively near shore, with the furthest being about an hour’s boat ride away. Aside from the wrecks, there’s also a healthy shallow-water reef and wall dives, offering the chance to see passing pelagics. The best time of the year to visit Rabaul is April through early January when the visibility is best and wind direction cooperates with dive boats.

Lissenung

Tiny Lissenung Island is home to a private resort right off the west coast of New Ireland Island, itself just north of New Britain Island. Visitors fly from Port Moresby to Kavieng, then it’s a 5-minute ride to the shore and a 20-minute boat ride to the resort, which sits just two degrees south of the equator, making for pretty consistent weather year-round. The island is only 1300 by 262 feet (400 by 80 m) and the resort sleeps a maximum of 16 guests, so you’re guaranteed seclusion. There are 36 mapped sites nearby, most well-known for pristine coral, sharks, turtles and macro life. Lissenung is best from late March through early January. Mid-January to mid-March is wet season and although you can still visit, it can get very windy and wet.

The post Dive Seasons in Papua New Guinea appeared first on Scuba Diver Life.

from Scuba Diver Life https://ift.tt/2xOHQZR

Friday, September 28, 2018

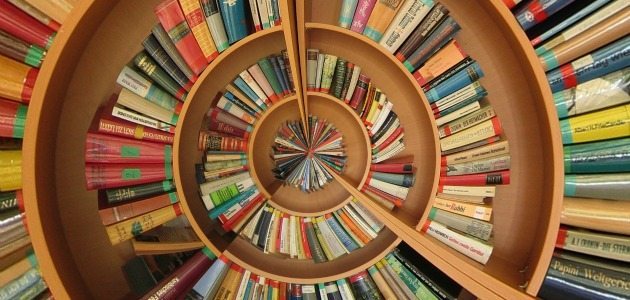

Books that make me feel better.

I’m drafting this post while keeping one eye on my Twitter feed: a stream of baffled, angry, scared, furious tweets from some of the smartest women I know who are going half insane trying to make sense of what’s happening with the Supreme Court right now.

Around 5 pm, the conversation shifts. Call-to-action quotes, exclamations about male privilege and cries of pain give way to the topic of healing, or at least of soothing.

Continue reading Books that make me feel better. at Diamonds in the Library.

from Diamonds in the Library https://ift.tt/2QgeI4C

An Underwater Photographer’s Guide to Southern Australia

When most divers think of Australia they think about the Great Barrier Reef, with its enormous size and huge diversity of animal and coral species. Indeed, the GBR is undoubtedly spectacular. However, the southern shores of Australia can offer some amazing experiences and views as well, especially for those photography addicts. Here are a few photography tips if you’re thinking of taking your camera down under to Southern Australia.

Seals

The southern coastline of Australia is dotted with hundreds of fur seal colonies, featuring members that are usually eager to get into the water for a swim and some games with a willing diver. Their willingness to hang around and their playful demeanor make fur seals ideal photographic subjects. Just be sure to turn up that shutter speed, as these hydrodynamic animals tend to sweep around you extremely quickly in graceful arcs, performing amazing feats of underwater contortion. If you can, jump on a boat and visit a colony. Seal tours operate all year round in dozens of locations — just remember the more fun you are, the more amazing the photo opportunities you’ll get with the equally playful seals.

Seadragons

Both leafy and weedy seadragons are definitely a highlight for any underwater photographer. You’ll find these endemic creatures all along the southern coastline, usually just offshore. Their vibrant colors and amazing camouflage can give your photos great contrast and color. Local dive shops can usually tell you the best places to go; it may even be worth hiring a divemaster for the day to help spot these animals. Although they can be almost 12 inches (30 cm) long, it still requires a keenly-trained eye to spot them hidden among the seaweed. Play with the camera’s aperture when you’re shooting seadragons to help achieve a background color that makes these unique creatures pop out of your photograph.

Shipwrecks

There are dozens of shipwrecks to explore and photograph throughout this part of Australia. Indeed, in Melbourne alone there are five different sunken submarines available to divers. Most large cities also boast a recent military wreck, purpose-sunk for divers. Lining up a diver next to the bow of a ship for some scale always makes for an interesting image. When photographing wrecks — especially when the visibility is average — a good wide-angle lens is essential to help you capture the ship on a grand scale.

Crabs

Animal migrations are one of the most amazing wildlife events you can capture with your camera. Thousands and thousands of creatures moving in unison, as though they have a single mind, can make for magnificent photography. Spiders crabs are one such animal. At roughly the size of a football, they emerge from the ocean depths once a year, migrating into shallow waters to molt their shells. When photographing a migration event, try out various angles with your camera to see which one can capture the true scope of the endless mass of animals you are seeing.

Sharks

Much of the water off Southern Australia is teeming with various shark species. From draughtboard and wobbegong sharks to curious and fearsome-looking grey nurse sharks, this part of the world presents some great shark-photography opportunities. Look in rocky crevices and along the ocean floor and you will likely spot a wobbegong or two resting. Covered in amazing military fatigue-like patterns and sporting tassels along their faces, they are one of the more unusual sharks. Grey nurse sharks, on the other hand, often congregate in colonies around caves and sandy trenches. At 6.5 to 10 feet (2 to 3 m) long and displaying row upon row of needle-like teeth, they can appear terrifying to a non-diver. They are, however, completely harmless. When diving with these animals, try to relax on the seafloor nearby. With luck, they will slowly swim over to investigate you, offering the perfect chance to snap a quick photo that is sure to become one of your favorites.

The post An Underwater Photographer’s Guide to Southern Australia appeared first on Scuba Diver Life.

from Scuba Diver Life https://ift.tt/2NPo1eU

MittMedia Q&A: 'We want to team up with companies that push us forward'

from World News Publishing Focus by WAN-IFRA - World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers https://ift.tt/2QhTUcZ

Wednesday, September 26, 2018

Training Fundamentals: Top Tips for a Successful Shore Entry

Depending on where you’re diving, you may find that the simplest way to enter the water is to walk right in. Below, we’ve compiled our top tips for executing a successful shore entry.

We can define shore diving as a dive where both the entry and exit take place from a shoreline, beach, jetty or quayside. This style of diving is incredibly popular in many parts of the world and is often more accessible than boat diving. If you have your own equipment, shore diving also allows you to dive independently with your buddy.

However, it’s often not simply a case of wandering off the beach into the water as the mood suits you. Shore diving has its own hazards and precautions you might take to ensure a happy, safe and successful day’s diving.

Do your research

In addition to regular pre-dive checks, if you’re diving at a commercially run lake or quarry you must often abide by specific rules, regulations and recommendations. Find out what they are and follow them. It may be something as simple as the lake’s opening time or closing time when all divers must be out of the water. Alternatively the lake may forbid solo diving, even for those qualified.

If you’re diving in the ocean, the winds, tides and currents are critical. Get it right and you’ll have a short walk to the water and a relaxing dive. Get it wrong and you could be fighting the tide or current. You could even have a more dangerous incident, potentially getting pushed away from your exit point despite your best efforts. Check wind forecasts and tide tables. Know the best time to enter the water, and if you’re unsure, check with a local dive shop.

Orient yourself to the area before you dive. Where is the best place to enter and exit the water? What are the potential hazards? Again, speak with the local dive center or club and experienced local guides. Certain shore sites have a natural area of rocky ‘steps’ that divers to access a convenient entry point. Or, they may have discovered that another area makes for a difficult exit due to rip currents. Note other factors such as surf and surge or concealed hazards beneath the surface, such as sharp rocks and urchins. Each factor impacts the exposure protection you choose, your route and what you bring on the dive (or leave behind).

Take what you need

It should apply to every dive but make sure you (and your buddy) have a DSMB and reel and know how to deploy them. At ocean shore-dive sites, you may need to make yourself visible to boat traffic or identify yourself to dive friends on shore. Similarly, always bring a cutting tool as rogue fishing line tends to be more prevalent at sea shore-dive sites on wrecks or underneath jetties. Taking cameras and accessories may be fun but tailor what you bring to safety. It’s all weight you’ll need to carry.

Bring some friends to wait for you on shore or, at the very least, advise someone not in the water when you intend to enter and exit water and to begin emergency procedures if you’re not back within a timeframe. At some dive sites, you may also need to advise the local harbormaster of your activities.

Entering the water

With a classic beach-diving shore entry, take some time to make a final environmental assessment before entering the water. Work through your pre-dive checklist and make sure that the conditions are safe for diving. Note entry and exit points. Take compass bearings and double-check that you have everything you need. Then, it’s time to buddy check and enter the water.

- Watch the wave cycle for a few minutes and note the interval between waves. Pay attention to the rhythm and get a feel for the best moment to enter the water.

- Ensure your jacket or wing is inflated as you enter. Always have your mask on and your regulator in your mouth during the initial entry.

- Enter the water close to your buddy either backward or sideways — never forward. Usually you’ll enter with fins on, except in exceptionally calm conditions, or on stony/rocky beaches. Keep close contact with your buddy and protect your mask with your free hand.

- Begin to shuffle backward, taking care with your balance and staying near your buddy. As you edge backward, glance over your shoulder and continue to monitor the conditions.

- As you reach swimming depth at waist height, time your final entry together through the surf or surge to coincide with a lull between wave cycles. If you haven’t yet donned your fins, now is the time to do so while holding onto your buddy for support.

- If more powerful waves hit your body, lean into it. Imagine you’re leaning into a strong gust of wind. Keep your legs apart to create a stable platform.

- Choose your moment and launch yourself quickly and assertively backward into the water between waves and don’t stop kicking. Try to be a speedy as you can to clear the initial surf zone until you reach an area of relative calm.

- When clear of the initial waves, roll onto your stomach and switch from your regulator to your snorkel as you learned in your open-water diver training to conserve air, unless you are ready to descend on the site at this point.

- If you feel tired from the initial entry, pause for a moment with your buddy and regain a normal breathing pattern before moving on. Overexertion may lead to anxiety and perceptual narrowing.

- Diving is a team activity so move at the slowest diver’s pace steadily to the final descent point.

Shore diving opens another avenue of diving and consequently, more wonderful diving experiences. The keys to a successful shore dive are planning and preparation. Gather all the information you need to remain safe and remember to plan the dive and dive the plan.

The post Training Fundamentals: Top Tips for a Successful Shore Entry appeared first on Scuba Diver Life.

from Scuba Diver Life https://ift.tt/2Ok1NBq

Working With Suicide Loss Survivors: We Have a Lot To Learn

from The New Social Worker Online — the professional social work careers magazine https://ift.tt/2xEDtR6

Tuesday, September 25, 2018

Voting Is Social Work: Voter Empowerment and the National Social Work Voter Mobilization Campaign

from The New Social Worker Online — the professional social work careers magazine https://ift.tt/2xCDnJx

Voting Is Social Work: The National Social Work Voter Mobilization Campaign

from The New Social Worker Online — the professional social work careers magazine https://ift.tt/2DsoajG

Monday, September 24, 2018

Crisis Centers: On the Front Line in Suicide Prevention

from The New Social Worker Online — the professional social work careers magazine https://ift.tt/2xKC7DF

Darwin and Wolf Islands: Gems of the Galapagos

On a highlight reel of diving in the Galapagos Islands, Darwin and Wolf Islands would be the undisputed stars. Unreachable except via liveaboard, these two legendary dive spots surpass even their fabled reputation. After two days at each onboard the Galapagos Master and a total of 15 dives, I finally know what all the fuss is about.

After a morning spent touring North Seymour Island and an afternoon dive at Mosquera, we begin the long overnight journey to Darwin and Wolf. Sitting at the far northwest of the archipelago, Wolf Island is about 173 miles (278 km) from Santa Cruz, the most heavily populated island in the chain. Darwin Island, our first stop, is a little further at 197 miles (317 km) away. Both these tiny rocks are completely uninhabited, and completely unreachable except via liveaboard. And even better, all the liveaboards in the Galapagos (there are only eight or nine in total), take turns visiting, so you’ll always be the only boat at the sites.

Darwin Island

The smaller of the two islands, tiny Darwin measures just .46 square miles (1.2 square km). Striated sand-colored cliffs rise out of the water, home to swooping, wailing frigate birds and their nests. We’re not here for Darwin Island itself, though. There’s really only one dive site — but not to worry — we really only need one. The unmistakable Darwin’s Arch is like nature’s version of the Eiffel Tower; even if you’ve never been, you’ll surely recognize its iconic visage.

Sitting less than a mile off the shore of the island, we’ll dive the arch over and over on our visit. Each dive starts out the same. We ride the pangas in groups of six out to the front of the arch, near the surge but not too close, and all backroll into the choppy water as one. We must make a speedy negative entry to avoid being swept off the site by the ever-present currents. “If you decide to go neutrally buoyant the ocean is going to take you out and take you out big-time,” says our dive guide Ruly Menoscal before our first dive.

He tells us that we needn’t go deep, only to about 60 feet (18 m) and that we needn’t move around a lot either. “If the activity is high, you don’t need to do much,” he says. “The hammerheads will come to you. All you need to do is turn on your camera.”

After our descent to the rocky slope below, we each tuck in behind a boulder, holding onto the barnacle-covered to keep from being swept away. It’s like an underwater amphitheater, with each diver occupying his seat as we all stare out to the stage before us, waiting for the show to start.

On dive after dive, we needn’t wait long — the curtain goes up as soon as we settle in. The explosion of life before us is hard to believe. Dozens of hammerheads face into the current just a few feet away, slowly undulating to hold their place. Among them are silky sharks, larger Galapagos sharks, countless clouds of reef fish and more green turtles than I’ve ever seen before on one dive — perhaps in my life. Turtles cruise by at a rate of a few per minute, so many that at one point I must duck to avoid getting clipped by one passing above my head. After about 30 minutes of hanging onto the rocks, Ruly gives the signal to let go and rise up, where we drift in among the sharks.

Our second dive is much the same, except for one superstar visitor: about 15 minutes into the dive, a small-ish whale shark swims by, not 20 feet (6 m) away from the divers. We all stare, google-eyed and yelling ecstatically into our regulators. Once we let go and begin to drift in the blue, it happens again, only this one’s a lot bigger and we’re right next to it. Again, I’ve got to duck to avoid touching the gentle giant’s belly as it passes right overhead. We surface, overjoyed, and feeling incredibly lucky since whale-shark season doesn’t technically begin until June and we’re here in May. We dive five more times on Darwin’s Arch and the star of the show appears at least twice more. As we get underway, I think nothing could equal the last two days — until we arrive at Wolf Island.

Wolf Island

Of the two dive sites, Darwin’s Arch is assuredly the more photogenic, at least topside, and rightly famous for whale-shark action. But rather than being an understudy in this production, I find Wolf Island to equal — if not surpass —Darwin when it comes to sheer underwater amazement.

Uninhabited Wolf Island is just marginally larger than Darwin at .5 square miles (1.3 square kilometers), but here there are at least five dive sites to choose from. The underwater topography resembles Darwin’s Arch, as does the dive profile. We backroll off the panga and complete a quick negative entry to the rocks below. Again, we tuck in between them to hide from the current and surge, holding onto barnacles for purchase. Where Darwin’s Arch is famous for whale sharks, Wolf Island wins for the equally quintessential Galapagos encounter: the ‘wall’ of hammerhead sharks. Divers tuck into the rocks and watch the blue, just as at the arch, but here it’s possible to look out and see hundreds of hammerheads at once, all facing into the current and slowly, slowly making their way past.

We eagerly jump in for our first dive at Shark Bay — and unlike many other dive sites named for an animal that never seems to appear — there are plentiful sharks on hand. We spot around 20 hammerheads, as well as Galapagos and silky sharks. The gang’s all here, but not in the numbers we’d hoped for. Bumphead parrotfish and dozens of moray eels appear as well — visitors that anywhere else would leave us agog elicit decidedly less enthusiasm in the Galapagos. But it’s not until the next day that Wolf really shows us what it’s got.

Early in the morning we dip into what the dive guides are calling “Red-lipped batfish bay” to search for these odd-looking creatures with distinctive, pouty red lips. They’re quite small and, other than their flashy lips, quite drab, blending in with the sandy bottom. We cruise along in about 70 chilly feet (21 m) of water, watching for them to scoot along on their pectoral fins, which they use more like arms. We spot three before the dive is over and it’s time for another dive at Shark Bay.

Although yesterday’s dive here was no doubt fantastic, it absolutely pales to what’s in store for us on our second day. We descend quickly in a raging current, quickly making our way to the hidey holes in the rocks. The current is so strong that smaller fish hide along with us and dozens upon dozens of turtles struggle to make any headway. After about 20 minutes, we make our way to a small pinnacle in the middle of the oncoming rush. We each find a handhold and wave like flags as life of all kinds flies by — hammers, Galapagos sharks, silkies, a tornado of schooling bonito. When we let go and make our way back to the rocks, the dive ends at a shallow turtle-cleaning station, where three sleeping turtles rock in the surge atop the flat bommie, about 12 feet from the surface, as tiny fish pick off parasites. It’s a safety stop we never want to end.

The dive guides have our final Wolf Island dive planned for a cave, but the whole group lobbies hard for another visit to Shark Bay — and it’s even more spectacular than the last. The current rages so hard that the wall of sharks before us can hardly move, clearly working hard to maintain their position on the fishy highway. Turtles have given up, drifting by with the flow. Once we, too, decide to just let go, we rise and rocket out into the blue — and straight into the wall of hammerheads. No longer spectators watching the movie, we’re now a part of it. Hundreds of sharks swim all around us, above us, underneath us, to our left and to our right. They part like a curtain as the current carries us away. The divers ascend, euphoric after a dive that everyone immediately counts as one of the best in their life.

After four exceptional days at Darwin and Wolf Islands, it’s time to move on — the rest of the Galapagos awaits.

The post Darwin and Wolf Islands: Gems of the Galapagos appeared first on Scuba Diver Life.

from Scuba Diver Life https://ift.tt/2DzSKYW

Saturday, September 22, 2018

NOAA Rolls Out New Online Resource for Florida Coral Disease Response

NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries is sharing a new online resource that provides information about the response to a coral disease outbreak in Florida.

The coral-disease outbreak began in 2014 and is unprecedented in geographic range, duration, high rates of mortality and the number of coral species affected. Nearly half of the stony coral species found on the Florida Reef Tract have been affected, including the primary reef-building species in Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary.

NOAA is calling this stony-coral tissue loss a disease because it only affects stony corals. NOAA is one of several agencies, academic, and non-profit organizations responding to the outbreak and Florida Department of Environmental Protection is the lead response agency.

This outbreak, and response, is ongoing. NOAA and the State of Florida have brought together coral experts to document the outbreak, identify the causes, understand the spread of the disease, and to identify and develop innovative, advanced treatments that may slow or stop the disease from spreading.

This web portal will be the primary location for public information about the Florida coral disease event.

The post NOAA Rolls Out New Online Resource for Florida Coral Disease Response appeared first on Scuba Diver Life.

from Scuba Diver Life https://ift.tt/2I57fCm

Thursday, September 20, 2018

Removing Invasive Seaweed Around Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary

There’s an invasion beneath the waves at Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary. It’s not an alien invasion — although the invaders themselves are green. Sargassum horneri, an invasive seaweed from Japan, has been replacing native algae in the sanctuary since 2009. In the past six years, its prevalence has shot through the roof. With this seaweed sprawling over the seafloor, who’s the sanctuary going to call?

They call Dr. Nancy Foster Scholar and “underwater landscaper” Lindsay Marks. For her PhD at the University of California, Santa Barbara, Marks extensively studies the fundamental ecology of S. horneri to try and predict how its growing presence will affect the ecosystem in Southern California.

Invasive seaweed is flourishing

According to Marks, S. horneri has several characteristics that make it a “really great invader.” It reproduces and matures quickly and can also self-fertilize to reproduce faster. If the parent plant gets dislodged, it can easily drift long distances and drop offspring as it floats along. The invasive algae can also thrive at depths where other species do not.

While the species living within ecosystems can change naturally, invasive species change the abundance and diversity of the native species. This change can leave an ecosystem less stable, which in turn can impact its economic benefits (like serving as a nursery for juvenile fish) and recreational offerings (like acting as an intriguing dive site). S. horneri is no exception.

Averaging 10 feet tall, S. horneri is shorter than the 60-foot native giant kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera) and cannot provide the same extensive habitat giant kelp does. Giant kelp houses several species in its canopies, including the valuable kelp bass. If S. horneri continues to replace the native seaweed, these kelp forests will look very different.

It does not taste good to herbivores like sea urchins, it grows really fast, and it reproduces like gangbusters,” says Marks. How, then, can the sanctuary stop S. horneri from spreading?

Tackling the problem

Marks tests how effective it is to remove the invader at Santa Catalina Island, just outside the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary. This is one of the first places S. horneri became really abundant. In 2016, Marks removed seaweed before the reproductive season and not only did she see a 25 percent reduction in the adult population, but she also saw a 50 percent reduction in new S. horneri plants.

While removal as a management strategy seems promising, the 2016 El Niño year tells a different story. The warmer waters it brought to Southern California favor the invasive seaweed, and the corresponding increase in S. horneri may provide a glimpse into future ocean conditions. With the steady increase of sea-surface temperatures, it is possible that the invasive seaweed will start to engulf the sanctuary, even with removal efforts.

Reason for hope

There is still a reason for ocean optimism. Long-standing marine-protected areas and no-take reserves, like those within Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary, are more resilient to the spread of S. horneri.

“In historical [marine protected areas] within the sanctuary, we see less of the invasive algae than we do in newer reserves that have not had enough time to recover from overexploitation,” Marks says. “There is some hope that well-preserved, healthy kelp forest communities do have the ability to resist these species.”

The logic goes like this: with protection and conservation, ecosystems can find balance within their food webs. For example, areas that have been protected longer have higher populations of kelp-forest predators, like lobsters. The lobsters, in turn, prey on sea urchins. Sea urchins are notorious for their ability to consume vast quantities of kelp, but they are kept in check when lobsters are around. But if lobsters are fished excessively, the urchin population balloons out of control. The many urchins can eat all of the native algae, making space for the invasive S. horneri to proliferate. In protected areas like national marine sanctuaries, resource managers can work closely with fishermen to ensure that enough lobsters and other predators remain to keep the ecosystem healthy.

Taking action

Instead of waiting for Southern California waters to recover over time, Marks is taking action. She worked with researchers at the University of California, Santa Cruz to create an information portal that documents the spread of S. horneri. She also created promotional materials — like fliers and videos — with California Sea Grant for recreational divers and boaters to help them identify the invasive algae, report it, and avoid spreading it. Marks has presented this information to the Channel Islands Sanctuary Advisory Council and stakeholders like dive clubs, in addition to posting fliers around harbors.

Currently, citizens can only harvest up to 10 pounds of invasive algae a day. But by educating the public, Marks is building an army of citizen scientists who care about the ocean and marine conservation. In the future, Marks hopes she can take citizen groups out into the water to participate in her underwater landscaping projects.

“People are very excited to learn about it. Every time I talk to divers about S. horneri, they are all gung ho to go out there and start removing it,” Marks says. “It’s definitely a dream of mine to keep working to control marine invasive species and harnessing the energy of citizens who want to help.”

By guest author Yaamini Venkataraman

Yaamini Venkataraman is a volunteer social media intern for NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries and a graduate student at the University of Washington.

The post Removing Invasive Seaweed Around Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary appeared first on Scuba Diver Life.

from Scuba Diver Life https://ift.tt/2DfiXvx

Wednesday, September 19, 2018

Preventing Veteran Suicides: Unique Challenges for Social Workers

from The New Social Worker Online — the professional social work careers magazine https://ift.tt/2xnpSNM

CME Corp Debuts Software Solutions to Automate Logistics, Direct-to-Site Services

CME Corp Debuts Software Solutions to Automate Logistics, Direct-to-Site Services

from CME Insiders https://ift.tt/2xAOmSS

Tuesday, September 18, 2018

Photographer Spotlight: Ron Watkins

In this series of articles, we’ll shine a spotlight on some of the world’s best underwater photographers. Today we highlight Ron Watkins.

Tell us a bit about yourself.

My father learned to dive in the 1950s and first ignited my passion and respect for the underwater world. When I was a teenager he took me diving in the cold, murky water of Lake Mead, Nevada and later in less-murky Southern California. From those early years, I knew that the ocean, diving and eventually photography would be major parts of my life. I have been increasingly using my photography and writing as a media to raise awareness and promote conservation because I have personally observed the decline over the last three decades.

Like many photo pros, I still have a career in the corporate world that I am not quite ready to leave completely. But I balance that with being a professional photographer, writer, trip leader and instructor, specializing in underwater photography.

How long have you been an underwater photographer?

I started taking pictures with film cameras about 25 years ago and in 1999 I took my first underwater photography class while on a live-aboard in Australia. After each day, we processed the slide film and the instructor critiqued my images. By the end of the trip, I saw significant improvements in my photos and entered my first photo contest. One of my shark images won first place in the SEASPACE 2000 international photo competition and after that, I did all I could to learn more about underwater photography and practice what I had learned. Since then, I have been published in over 15 magazines around the world and recognized in multiple competitions.

What got you interested in underwater photography?

As I mentioned before, my dad introduced me to diving and we shared that passion together for many years. When a medical issue forced him to stop diving, I got into underwater photography as a way for us to still have that bond. After my dive trips, I would show him the images and share stories about the diving, the trip and interesting people I met along the way. Even in his 80s, he still loves to reminisce about our early days diving together and his time in the Navy on the USS Oriskany. Every time we say goodbye, he always tells me to “have fun diving and be safe.”

What’s your favorite style of underwater photography?

That is very hard to say but lately I have been focused on mostly wide-angle, although I thoroughly enjoy all types of UW photography. I consider myself a bit of a jack-of-all-trades, which has really helped me in my UW photography workshops because I am able to teach basic and advanced techniques in macro, super macro, snooting, close-focus WA, split shots, ambient light, working with models, and other more creative techniques.

Any favorite subjects?

In recent years, I have been planning my trips around the larger animals like crocodiles, whales and especially sharks because they are under such pressure around the world from shark finning, commercial by-catch and shark fishing. A recent passion project of mine was to photograph salmon sharks in Alaska to learn more about them and increase awareness of their struggles. I first saw one in Southern California waters and it wasn’t until four years later that I was able to get my first pictures after multiple trips to Alaska.

Any favorite destinations?

My answer changes over time but usually it is one of the recent places I have been. I really learned to appreciate California diving while living there for five years (after I got a good wetsuit and drysuit to stay warm). California has great marine diversity, including sea lions, sharks, tons of nudibranchs, kelp forests, and jellyfish. Keeping with the cold-water theme, I also love diving in British Columbia, Canada at God’s Pocket and Alaska where in addition to the elusive salmon shark, there are huge blooms of jellyfish, giant plumose anemone gardens, critters galore and salmon in the streams.

For warmer water, it’s hard to beat the marine diversity and healthy reefs of the Coral Triangle. For big-animal photography, it is hard to beat the consistently crystal-clear waters of French Polynesia, which are teaming with sharks year-round. And how can I forget the marine-protected waters of the Gardens of the Queen in Cuba, where pristine Caribbean reefs look the way they were 60 years ago, teaming with sharks and American crocodiles. For local diving, the up-close-and-personal mako and blue sharks of Rhode Island make for an action-packed photography trip.

What’s your underwater setup?

I recently upgraded from a Nikon D800 full frame DSLR to the Nikon D850 and absolutely love the 3D-focus mode speed and accuracy, the dynamic range and quality of the images captured on that sensor. For wide-angle lenses, I use the Nikor 16-35mm and 8-5mm circular fisheye lenses and for macro, I use both the 105mm and 60mm Nikor lenses. The camera is housed in Nauticam with a large 9-inch Zen glass dome port. My rig also sports two fast powerful Sea & Sea YS250 strobes for wide-angle big-animal action. For macro I switch to my Sea & Sea D2J strobes with a Retra LSD snoot and OrcaTorch 900V focus/video light.

Do you have any tips for new underwater photographers?

Other than the obvious — hone your dive skills before ever touching a camera — here are my top three tips!

Take an underwater photography workshop. Why struggle, trip after trip, trying to teach yourself how to use your new equipment and troubleshoot why your pictures aren’t coming out the way you want them to? You spend a lot of money on the equipment, travel and precious time off from work, so why not spend a few more bucks to reduce your frustration levels and accelerate your learning curve?

Know your gear inside and out before you ever get in the water. It is not the camera that takes the picture—it’s you. Read your manual and learn all the camera’s options, then experiment with them. Look online for underwater reviews and tips for your model. This will pay dividends on your trip and significantly reduce your learning curve.

Finally, don’t take yourself or your photography too seriously. Obviously, you need to be serious about the learning process if you want to improve. But don’t judge the quality of the dive or trip by the pictures you get. Some photographers get to be real sour pusses if they don’t get “the shot” and especially if someone else does. Have fun diving, taking pictures and enjoying the beauty of the underwater world. Work on your underwater photography skills. With time, your consistency and quality of images will improve and you’ll be ready to capture that one in a million opportunity when it appears.

By guest author Ron Watkins

For more of Ron Watkins’ work, please visit his website here, Facebook, or Instagram.

The post Photographer Spotlight: Ron Watkins appeared first on Scuba Diver Life.

from Scuba Diver Life https://ift.tt/2NmbqzF

Monday, September 17, 2018

Autism and Suicide: Reducing the Risk

from The New Social Worker Online — the professional social work careers magazine https://ift.tt/2pexkqb

Sunday, September 16, 2018

Self-Care A-Z: Notorious RBG (Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg) Builds a Case for Self-Care

from The New Social Worker Online — the professional social work careers magazine https://ift.tt/2NQsZHq

The Greatest Hits of the Galapagos Islands

“You’ve got to respect the place that you are diving. The Galapagos Islands are like nowhere else.”

So says Ruly Menoscal, the lead guide on my 10-day cruise aboard the Galapagos Master. And boy is he right — diving in the Galapagos is like an all-you-can-eat buffet of only your favorite dishes. There’s no throwaway coleslaw or potato salad here. On our trip, the closest we come to a so-so dive is our check-out in the harbor of San Cristobal, where there’s little coral and a sandy bottom without much to see — until two of the harbor’s resident sea lions join us in about 30 feet of water. After 20 minutes underwater, I’m hooked.

Only four of the 21 islands are inhabited, which leaves most of 3,093-square miles (8,000 square km) completely untouched. This makes for a raw, wild landscape and little to no run-off in the water. Even better, three ocean currents — the cold South Equatorial Current (the source is the Humboldt Current), the warm Panama Current, and the cold, deep Cromwell Current — converge in the Galapagos, creating arguably the world’s richest marine environment.

Now boarding the Galapagos Master

I meet the other divers for my cruise at the small, easily navigable airport in San Cristobal. There’s excited chatter in several languages on the bus to the harbor — there are Germans, Swiss, English, French and Canadian divers on board — in fact, I’m the only American. On our stroll down the pier, the sound and sight (though maybe not the smell) of at least 100 sea lions, lolling on the harbor rocks delights me. After a short ride out, we board the waiting boat.

There are 12 staff onboard, including our chef Angel, pretty much always my favorite crewmember. Our guides Raul (who goes by Ruly) and Jimmy have been on the boat for varying amounts of time. Guides here are freelancers, moving from boat to boat, working a few weeks on, a few weeks off. Each of ours has thousands of hours underwater in the islands though, so we’re in good hands. We take a quick look at the dive deck before heading inside the boat, first through the dining area and then past a large camera station, and finally into the salon, occupying the bow of the boat. Wide, comfortable looking blue banquettes and a few comfy-looking beanbag chairs beckon, but first it’s downstairs to check out my cabin.

There are four cabins on the lower deck and four on the upper deck, and mine is more than roomy enough. I’ve got no roommate, so I use the extra twin bed for storage and guiltlessly claim every hanger in the armoire. After unpacking — tip: bring more comfy clothes than you think you’ll need — we head upstairs for a short tour before the boat briefing. On the upper deck, occupying the aft of the boat, is a large, shaded seating area, with even more beanbags and comfy couches. Up one more level is the sun deck where I find — you guessed it — more beanbag chairs, a cocktail bar, and a fantastic 360-degree view. No time to enjoy it yet, though; first it’s time for the boat and dive briefings.

Each day except the first two will feature three or four dives; today we just had time for our checkout, and tomorrow we’ll dive once in the afternoon after an island walk. I’m equally excited for both and head downstairs early to get some sleep for what’s sure to be a full day.

North Seymour Island

Divers on Galapagos liveaboards are allowed two visits to land: we use our first the next morning on North Seymour Island, a small, uninhabited spot that’s positively bursting with life. A few hours’ nature walk along a signposted route (leaving the path is not allowed) introduces us to iconic blue-footed boobies, nesting frigate birds, sunbathing iguanas and dozens of sea lions, from small pups to burly bulls.

Although there is some tree cover on North Seymour, the landscape of the islands themselves is generally stark. It’s all volcanic rock, with little tufts of greenery and patches of low trees. There are no big land mammals in the Galapagos; there’s simply not the environment to support them. But the animals here — and there are many — have thrived since the islands became a protected national park in 1959.

After completing the loop path and snapping dozens of pictures, we’re heading back to the boat for our first “real” dive. As we’re leaving, a few more groups of tourists arrive for walks of their own. One of them asks me if it’s worth it, to which I chuckle softly and reply, “Oh yes. Yes, it is.”

Diving in Galapagos

As Ruly said from the get-go, you’ve got to respect the place you’re diving. Marine life in Galapagos is spectacular, but you’ve got to earn it with potentially challenging conditions, so I follow the briefing closely, admittedly a little nervous about back-rolling with a negative entry into potentially strong current. On our trip, we’ll have up to 27 dives, including two full days each at Darwin and Wolf Islands, followed by days at Isabela, Fernandina, Cabo Marshall and Cousins Rock.

Although the boat can easily accommodate 16 divers, our group is small at 12, so we split into two groups of six. We dive via two pangas, taking turns going first; always at the same dive site but never crowded together.

We gear up and get ready for our first “official” dive in the Galapagos in the channel between tiny Mosquera Island and Baltra near North Seymour. After 50 minutes underwater, I’m filled with awe. We drop down on some sloping boulders that front a nice sandy patch and almost immediately there’s a small school of scalloped hammerheads along with a giant blacktip shark. There are countless turtles, giant schools of fish, eagle rays, scalloped hammerheads, the blacktip, turtles —sometimes all at the same time. We drift along with the boulders to our right and level up from 70 feet to about 50 where the current catches us. Up and over the boulders we go, flying along in about 12 feet of water on an extended safety stop.

Once we’re all back onboard, it’s time to begin the overnight journey to the legendary Darwin and Wolf Islands, where there’s simply too much to cover here. Stay tuned for another story focusing exclusively on these legendary dive sites.

Dive, dive, dive

After four full days at Wolf and Darwin, we move on to our next site, Punta Vicente Roca, off the northwest coast of seahorse-shaped Isabela Island. It’s the largest in the island chain, formed by six active volcanoes. The site sits right on the seahorse’s lower jaw. Unfortunately, however, I’ve developed a cold overnight and can’t clear my ears for the dive, which will be relatively deep and involve a search for the site’s iconic residents — mola mola.

I’m gutted, but my panga driver Javier graciously putters me around the bay while the divers are down, looking for tell-tale signs of molas at the surface. We luck out and spot a few, so I slip as quietly as possible into the water to get a peek. I’m rewarded with brief glimpses of these famously shy fish before they disappear into the deep. Not to be outdone, the bay’s resident sea lions come to play with me on the surface as well. They dive-bomb and twist around me, matching their play with my own level of enthusiasm. For a non-dive day, I couldn’t be happier.

Next up is Cabo Douglas, home of another famous Galapagos resident: marine iguanas. These ingenious, endemic reptiles have figured out that the algae encrusting the boulders just offshore is a fantastic food source. Each day at mid-morning, after the sun has warmed the chilly water a bit, they slip beneath the surface to munch on the algae below. They grip the rocks with their strong claws, spending up to 40 minutes underwater to feed before coming up for a gulp of air and submerging again.

“It’s a 40-minute safety stop” says Ruly of the site, where divers will spend as long as they can in chilly water only 10 to 15 feet deep (3 to 5 m). And I’m lucky that it is, because my ears still aren’t cooperating. “They’re feeding, so don’t disrespect them,” says Ruly, right before we roll into the water. I hover on snorkel above the eating iguanas, nearly as close as the divers below, who’ve been told to maintain a 5-foot (1.5 m) distance. The iguanas are nonplussed by our presence, rising to the surface and cruising back to the shore like surfers gracefully riding a wave when they’re done with their meal.

We spend our final dives of the trip at Cabo Marshall to see mantas and Cousins Rock, famously a photographer’s dream site for sheer volume of life. My dive trip is over, however, and I’m relegated to snorkel. I’m simultaneously happy for excited divers emerging from the water and jealous that I wasn’t with them. My unfortunate cold has mostly, however, strengthened my resolve that I must return.

Life aboard the Master

As with all liveaboards, we fall into an easy rhythm on the Master. We wake, eat a light breakfast, dive, eat a full breakfast, dive, eat lunch, have a nap and a snack, dive, and eat dinner. Repeat. If there’s a diver in the world who doesn’t love a routine like that, I haven’t met him. Most of the guests spend the afternoon on the upper deck, filled with comfy chairs and couches and exposed to the air but thoughtfully covered to keep the sun at bay. As we move, frigate birds fly alongside the ship, gracefully gliding in and out of the breeze and alighting on the bow when we stop.

Silky sharks join us as well, showing up just downstream of the galley shortly after we anchor. Slowly undulating in the water below, they’re almost as excited for meal times as we are when the galley flushes out organic waste. Aside from our final land excursion in Santa Cruz and our walk on North Seymour, we don’t see another soul for 10 days, either on the islands or on a dive site — and it’s simply glorious.

Tortoise time on Santa Cruz

On our final day, we make the second land excursion to Santa Cruz. It’s by far the busiest island in the Galapagos with a population of around 12,000. We’re meant to go to the Darwin Research Station to see giant tortoises, but instead detour to Rancho el Manzanillo, a privately-owned farm where dozens of tortoises roam free. Ruly gives us a brief talk in the onsite restaurant about the tortoises’ ecology and history and guides us on a short walk before turning us loose to wander the paths and forested area in search of giant tortoises on our own.

I happen upon a pair munching quietly in the shade and settle in near a tree to watch them, remaining as unobtrusive as possible. Despite their size, they spook easily and do not care for close human contact. After about an hour, it’s time to head back to the boat and begin the journey back to San Cristobal, from where we’ll disembark the next day.

Details

With eight cabins, the Galapagos Master can accommodate 16 guests. Cruises are either seven or 10 nights; longer itineraries get two full days at each Darwin and Wolf Islands. You’ll want to be nitrox certified before you go, as there’s no training offered on board. Make sure you’re comfortable in potentially strong currents as well — bring an SMB and know how to use it.

How to get there:

To reach the Galapagos Master, you’ll initially fly into either Quito or Guayaquil; plan on an overnight in whichever city you choose the night before your flight on to San Cristobal. If you book your domestic flight directly with Master Liveaboards, a company representative will meet you at the airport before your flight to San Cristobal to walk you through the process. In Quito there’s a separate check-in area for the Galapagos where they’ll screen your bags and attach green zip-ties once they’re through. You’ll then proceed through security as usual.

On arrival in the Galapagos you’ll pay a $100 national park fee (in cash) before boat representatives whisk you away for the trip of your dreams.

When to go:

There’s no bad time of year to go to the Galapagos; it just depends on what you most want to see. The most popular time of year understandably is whale-shark season, from June through November. During this time divers can see up to a dozen whale sharks on one dive at Darwin’s Arch. It’s not impossible to see these giants at other times, however; I visited in April and saw them on three separate dives. This season brings cooler water conditions, so plan accordingly.

From December through May the water is warmer, typically from 78 to 82 F (25 to 27 C), and there are more mantas, and other rays, around Wolf and Darwin Islands. This is typically the best season to see the iconic “wall of hammerheads” at Wolf Island as well. I was there in May, however, and the water was slightly colder, topping out at 75 F (24 C) and cooler at depth. Although we didn’t see mantas, we did see whale sharks and tons of hammerheads.

The post The Greatest Hits of the Galapagos Islands appeared first on Scuba Diver Life.

from Scuba Diver Life https://ift.tt/2D2m9dP